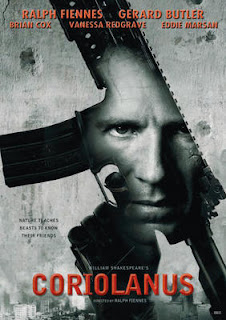

Ralph Fiennes makes his debut as a director and stars in "Coriolanus", adapted from the Shakespeare tragedy. Fiennes plays Roman general Caius Martius. We meet him as he quells grain riots at home and leads a siege and assault abroad, against Rome's Volscian enemies on a Balkans-like urban battlefield. Martius is soaked in the blood of his enemies and seems at the height of his powers, pushing himself and exhorting his men. He clashes in single combat with Aufidius (Gerard Butler), the Volscian commander and Martius' mortal enemy, until they are dragged apart. Everything we see shows Martius as tireless and relentless. What is driving him?

At home he is received as a hero and honored with a new name of Coriolanus. The home front wants a piece of him. First, his mother Volumnia (Vanessa Redgrave) and politician Menenius (Bryan Cox) maneuver to have him elected consul. He reluctantly agrees. He is approved by the Senate, but a popular riot is instigated by a rival faction. Martius is humble under praise, but explosively defensive under criticism - Fiennes' proud anger is something to behold. Martius is provoked to fury at the mob, and ultimately exiled. He journeys to his rival Aufidius, and offers his life or his services against Rome.

In every case when someone tries to use Martius for their own ends, trouble follows. The efforts to use Martius as a political figurehead, the successful conspiracy to oust him, and Aufidius' decision to retain him all bring mess that compounds towards tragedy. It seems most remarkable that Aufidius, who perhaps would know Martius' motivation better than most, would agree to fight alongside him. Butler doesn't have a huge amount to do in the film, but he sells well Aufidius' dilemma, weighing whether he can get the better of Martius, using him while plotting his subsequent demise.

By now it is clear that Martius cannot be changed, so either he must succeed in his revenge or be stopped. Redgrave displays Volumnia, sent with Martius' wife and son to try to stop him, beseeching in physical and emotional waves. Redgrave and Fiennes are captivating. Where Martius at war circled and parried when fighting Aufidius in battle, now he is pinned to his chair by Volumnia, bearing her relentlessness that seems so much like his own.

Despite the crackling dialogue in this confrontation and throughout the film, I found the most satisfying scenes those where we observed Martius alone: sweeping through a shell of a building in the opening combat, and hiking into exile away from Rome and to Aufidius. It is never quite explained why he is blamed for the grain riots that open the film, but he is unwavering in his self-belief, so we are forced, like the people, to take him or leave him without debate. His world is black and white, with only one correct, honorable path. When we see Martius with others they fill the scene with words, talking to, at or about him. Their words are bound to provoke him. Alone nothing disturbs him from within: he simply moves forward.

Links: IMDb, Metacritic

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

Monday, September 26, 2011

God Bless America (2011)

Bobcat Goldthwait's "God Bless America" played in the inimitable Midnight Madness at this year's TIFF. Maybe it's just safer to use Canada to open a story of a blood-soaked killing spree motivated by the alleged base evil of American popular culture. Thankfully the Midnight Madness stamp helps as a reminder not to take premises too seriously. I watched it as a caper rather than a satire, which is most definitely what I would recommend.

Frank (Joel Murray) is divorced and lives alone through a duplex wall from his loutish neighbors and their perpetually screaming baby. He fantasizes violence against them. He has trouble sleeping. His routine is to take sleeping pills and slump in insomniac stupor in front of a TV that shows shrill wall-to-wall reality TV: we are treated to broad parodies of the state of the art of that genre. The Kardashians come in for particularly harsh treatment. The targets are easy, but the jokes are so relentless that it doesn't matter.

At work Frank's colleagues spout recycled soundbites from talk radio and discuss the film's version of "American Idol". He fantasizes violence against them too. Frank delivers a blistering, eloquent, whining rant to his cubicle mate on incivility and stupidity. We are in wish-fulfillment territory, Frank our champion against the vapidity of mass media culture. Then Frank is fired, and somehow this is the best joke so far. Where a film like "Idiocracy", with similar targets but a different approach, asks little more than that we agree that everything and everyone is stupid, Frank's outsize misanthropy is occasionally challenged and skewered. Worse is to come: his migraines are apparently the product of a brain tumor. His young daughter is beginning to bear an unnerving resemblance to the entitled teenaged star of one of the reality TV shows on his insomniac dial.

Frank steals his neighbors' car, drives through the night, and kills the star. We're off! He intends to kill himself too, but he is interrupted by Roxy (Tara Lynne Barr). She saw the killing, she approves, and she wants to join Frank to deliver more "justice" to the ignorant and undeserving. The two embark on a spree that allows us to celebrate grisly comeuppance for everyone from loud moviegoers to thinly disguised Fox News hosts. Joel Murray cuts the misanthropy with a squinting, grumpy wryness that plays happily against Barr's wiseass teenager. The relationship is firmly paternalistic. Frank's principles come in handy in ruling out less savory undertones - as he makes clear to Roxy, he includes sexualization of children among society's crimes.

"God Bless America" lives in the differences between Frank and Roxy. The two killers are in constant discussion over the criteria for victims. Roxy errs on the side of killing pretty much everyone. Her nihilistic teenage bluster allows Frank to display his principles, and those principles in turn let her push at the logical boundary of his absolutism. They make a great pair. Their defining exchange is Roxy putting "anyone who gives high fives" on her list of the guilty; Frank quite likes high fives and is disappointed. That they are not the same means that we can't see the film purely as a universal rant for the smugly superior. Then we are free to simply tag along and enjoy the what-the-hell fun of the spree against their common enemies.

The man-and-girl team naturally recalls "Super", itself a 2010 TIFF Midnight Madness pick. In that film Rainn Wilson was driven to fantastic violence, with Ellen Page his young sidekick. But where Super's protagonist was driven to insane heights by personal vengeance, here Frank is motivated by a much broader, matter-of-fact hate, and at no point is he allowed wild-eyed craziness. This helps: Frank can stand in for us, and the shocking violence can be our shocking violence, which I think makes it a bit less shocking. Of course it also helps that "God Bless America" has excellent jokes.

Links: IMDb

Frank (Joel Murray) is divorced and lives alone through a duplex wall from his loutish neighbors and their perpetually screaming baby. He fantasizes violence against them. He has trouble sleeping. His routine is to take sleeping pills and slump in insomniac stupor in front of a TV that shows shrill wall-to-wall reality TV: we are treated to broad parodies of the state of the art of that genre. The Kardashians come in for particularly harsh treatment. The targets are easy, but the jokes are so relentless that it doesn't matter.

At work Frank's colleagues spout recycled soundbites from talk radio and discuss the film's version of "American Idol". He fantasizes violence against them too. Frank delivers a blistering, eloquent, whining rant to his cubicle mate on incivility and stupidity. We are in wish-fulfillment territory, Frank our champion against the vapidity of mass media culture. Then Frank is fired, and somehow this is the best joke so far. Where a film like "Idiocracy", with similar targets but a different approach, asks little more than that we agree that everything and everyone is stupid, Frank's outsize misanthropy is occasionally challenged and skewered. Worse is to come: his migraines are apparently the product of a brain tumor. His young daughter is beginning to bear an unnerving resemblance to the entitled teenaged star of one of the reality TV shows on his insomniac dial.

Frank steals his neighbors' car, drives through the night, and kills the star. We're off! He intends to kill himself too, but he is interrupted by Roxy (Tara Lynne Barr). She saw the killing, she approves, and she wants to join Frank to deliver more "justice" to the ignorant and undeserving. The two embark on a spree that allows us to celebrate grisly comeuppance for everyone from loud moviegoers to thinly disguised Fox News hosts. Joel Murray cuts the misanthropy with a squinting, grumpy wryness that plays happily against Barr's wiseass teenager. The relationship is firmly paternalistic. Frank's principles come in handy in ruling out less savory undertones - as he makes clear to Roxy, he includes sexualization of children among society's crimes.

"God Bless America" lives in the differences between Frank and Roxy. The two killers are in constant discussion over the criteria for victims. Roxy errs on the side of killing pretty much everyone. Her nihilistic teenage bluster allows Frank to display his principles, and those principles in turn let her push at the logical boundary of his absolutism. They make a great pair. Their defining exchange is Roxy putting "anyone who gives high fives" on her list of the guilty; Frank quite likes high fives and is disappointed. That they are not the same means that we can't see the film purely as a universal rant for the smugly superior. Then we are free to simply tag along and enjoy the what-the-hell fun of the spree against their common enemies.

The man-and-girl team naturally recalls "Super", itself a 2010 TIFF Midnight Madness pick. In that film Rainn Wilson was driven to fantastic violence, with Ellen Page his young sidekick. But where Super's protagonist was driven to insane heights by personal vengeance, here Frank is motivated by a much broader, matter-of-fact hate, and at no point is he allowed wild-eyed craziness. This helps: Frank can stand in for us, and the shocking violence can be our shocking violence, which I think makes it a bit less shocking. Of course it also helps that "God Bless America" has excellent jokes.

Links: IMDb

Sunday, September 25, 2011

Moneyball (2011)

Michael Lewis' book "Moneyball" was published in 2003. For years afterwards Joe Morgan, ESPN's leading baseball color commentator, repeatedly insisted that the book had been written by Billy Beane. This is absolutely nonsensical. But now that "Moneyball" has made it to the big screen, Morgan's nonsense be a tiny bit less ridiculous: this is most definitely now the Billy Beane story. Can a person be a success if he is not the best?

The book painted a detailed picture of the lineage of the then state-of-the-art in the analysis of baseball players through the lens of the 2002 Oakland A's and their general manager Billy Beane (Brad Pitt). Bennett Miller's movie condenses the story of the gradual revolution in analysis into an adapted story of that one season, using it as the backdrop to its relaxed portrait of a man driven by hatred of losing. To get away with this, the film stereotypes the peripheral baseball figures around Beane in a way that the book was careful not to, but I had no problem there. Who needs fidelity from a baseball movie, let alone one about player valuation? This goes also for the liberties taken in illustrating the 2002 A's without so much as mentioning their MVP shortstop or three elite starting pitchers. So be it.

Instead we are left with the character of Beane, composed entirely of his relationships to baseball and his young daughter Casey (Kerris Dorsey). We first see him sitting alone in stands of the dark Oakland Coliseum as his team, on the other side of the country in Yankee stadium, loses in the first round of the 2001 playoffs. He cannot even stand to listen to the radio he is holding, flicking it on and off. He is drained by defeat, but he is not there to witness it. It is the endpoint of success or failure that affects him, not the way it is earned. "We lost", he says repeatedly, refusing any consolation.

His challenge then is to rebuild the team after this disappointment - and the loss of several key players to other teams and the big-money contracts he and his A's cannot afford. Pitt plays Beane almost manically, in his drive to win at one moment cool and focused and the next shooting from the hip. He senses that he cannot replace his lost stars in any straightforward sense of the word. He notices and then poaches a young analyst, Peter Brand (Jonah Hill), from a rival team's administration, elevating the data-cruncher to be his right-hand man. Together they forge a plan to punch above their weight, to find value in the darkest corners that richer teams can afford to overlook. Brand has little obvious motivation other than his correct conviction that the conventional wisdom is wrong; Beane's motivation is enough for two men.

Pitt's relationship with Jonah Hill occasionally recalls that with Ed Norton from "Fight Club", as Beane mentors Brand by challenging and wrong-footing him. But Brand talks back. Through their discussions we see that Beane is credulous and does not struggle against what, to the old-school baseball lifers that compose his staff, is sacrilege. Eventually he even descends to explain himself to his players, teaching his misfits how they can achieve the success that Brand has convinced him they can attain. Still he will not watch the games, but neither is he sitting alone in an empty stadium. He is now intervening in fate.

Beane's tragedy throughout is that he cannot conceive of exceeding expectations as success. It's not enough for his team to do better than they "should", given their resources. The point is driven home by interspersed scenes of the young Beane, a supposed sure-fire baseball star, not the underdog but the favorite. He flames out, fails, and there is no space for him between this failure and that. Later, Brand tries to demonstrate to Beane that progress, and beating the odds, is not failure, at worst a different kind of success; Beane seems to concede in principle without quite agreeing.

It is another story entirely with his daughter. Baseball consumes the vast bulk of the screen time, but in a sense Beane's most important relationship in the film is with his Casey. He takes her to buy a guitar. She plays well and he asks her to sing too, but she is reluctant - she's not very good, she claims. But now it doesn't matter to him. He convinces her to sing, and she is good, better than we could expect, and Beane is speechless and proud. Suddenly the question of who is the best singer doesn't matter; Casey is good, and Beane cares about Casey.

Pitt's performance is too subtle and the film as a whole too patient for melodrama or triteness. Yet by the coda when Beane is invited to ascend to the throne as general manager to the Red Sox, to suddenly have a buffer of the resources as well as the drive to win, it seems that more than just being close to his family or a perverse desire to be the underdog drives him to decline. Perhaps Beane, without ever quite admitting it, is now willing to admit that different kind of success.

Links: IMDb, Metacritic

The book painted a detailed picture of the lineage of the then state-of-the-art in the analysis of baseball players through the lens of the 2002 Oakland A's and their general manager Billy Beane (Brad Pitt). Bennett Miller's movie condenses the story of the gradual revolution in analysis into an adapted story of that one season, using it as the backdrop to its relaxed portrait of a man driven by hatred of losing. To get away with this, the film stereotypes the peripheral baseball figures around Beane in a way that the book was careful not to, but I had no problem there. Who needs fidelity from a baseball movie, let alone one about player valuation? This goes also for the liberties taken in illustrating the 2002 A's without so much as mentioning their MVP shortstop or three elite starting pitchers. So be it.

Instead we are left with the character of Beane, composed entirely of his relationships to baseball and his young daughter Casey (Kerris Dorsey). We first see him sitting alone in stands of the dark Oakland Coliseum as his team, on the other side of the country in Yankee stadium, loses in the first round of the 2001 playoffs. He cannot even stand to listen to the radio he is holding, flicking it on and off. He is drained by defeat, but he is not there to witness it. It is the endpoint of success or failure that affects him, not the way it is earned. "We lost", he says repeatedly, refusing any consolation.

His challenge then is to rebuild the team after this disappointment - and the loss of several key players to other teams and the big-money contracts he and his A's cannot afford. Pitt plays Beane almost manically, in his drive to win at one moment cool and focused and the next shooting from the hip. He senses that he cannot replace his lost stars in any straightforward sense of the word. He notices and then poaches a young analyst, Peter Brand (Jonah Hill), from a rival team's administration, elevating the data-cruncher to be his right-hand man. Together they forge a plan to punch above their weight, to find value in the darkest corners that richer teams can afford to overlook. Brand has little obvious motivation other than his correct conviction that the conventional wisdom is wrong; Beane's motivation is enough for two men.

Pitt's relationship with Jonah Hill occasionally recalls that with Ed Norton from "Fight Club", as Beane mentors Brand by challenging and wrong-footing him. But Brand talks back. Through their discussions we see that Beane is credulous and does not struggle against what, to the old-school baseball lifers that compose his staff, is sacrilege. Eventually he even descends to explain himself to his players, teaching his misfits how they can achieve the success that Brand has convinced him they can attain. Still he will not watch the games, but neither is he sitting alone in an empty stadium. He is now intervening in fate.

Beane's tragedy throughout is that he cannot conceive of exceeding expectations as success. It's not enough for his team to do better than they "should", given their resources. The point is driven home by interspersed scenes of the young Beane, a supposed sure-fire baseball star, not the underdog but the favorite. He flames out, fails, and there is no space for him between this failure and that. Later, Brand tries to demonstrate to Beane that progress, and beating the odds, is not failure, at worst a different kind of success; Beane seems to concede in principle without quite agreeing.

It is another story entirely with his daughter. Baseball consumes the vast bulk of the screen time, but in a sense Beane's most important relationship in the film is with his Casey. He takes her to buy a guitar. She plays well and he asks her to sing too, but she is reluctant - she's not very good, she claims. But now it doesn't matter to him. He convinces her to sing, and she is good, better than we could expect, and Beane is speechless and proud. Suddenly the question of who is the best singer doesn't matter; Casey is good, and Beane cares about Casey.

Pitt's performance is too subtle and the film as a whole too patient for melodrama or triteness. Yet by the coda when Beane is invited to ascend to the throne as general manager to the Red Sox, to suddenly have a buffer of the resources as well as the drive to win, it seems that more than just being close to his family or a perverse desire to be the underdog drives him to decline. Perhaps Beane, without ever quite admitting it, is now willing to admit that different kind of success.

Links: IMDb, Metacritic

Saturday, September 24, 2011

Violet & Daisy (2011)

I saw "Violet & Daisy" at TIFF, where after the screening an audience member let Geoffrey Fletcher know that "Tony Soprano" was perfect for the role of Michael. This seems to me to be a horrific insult to James Gandolfini. His Michael is the gravity at the center of Fletcher's film. When Michael arrives in the film, he pulls the title characters to a standstill, his apartment, where the majority of the action takes place, slow and quiet against the chattering pace that Violet and Daisy have established. Gandolfini plays Michael with his special kind of heaviness, but there is not an ounce of danger or volatility.

I saw "Violet & Daisy" at TIFF, where after the screening an audience member let Geoffrey Fletcher know that "Tony Soprano" was perfect for the role of Michael. This seems to me to be a horrific insult to James Gandolfini. His Michael is the gravity at the center of Fletcher's film. When Michael arrives in the film, he pulls the title characters to a standstill, his apartment, where the majority of the action takes place, slow and quiet against the chattering pace that Violet and Daisy have established. Gandolfini plays Michael with his special kind of heaviness, but there is not an ounce of danger or volatility.Violet (Alexis Bledel) and Daisy (Saoirse Ronan) are teenage contract killers. We meet them disguised as nuns, cracking wise while blasting improbably through a bunch of adversaries to rescue someone or other. So far, so Tarantino. They are excruciatingly childlike, playing pat-a-cake, accepting the next job only because they need money to buy the latest dresses from a pop star's clothing line. We seem established in a familiar place, from where the two girls can go on an improbable, guns-blazing adventure.

But it is not to be: the target of the job they accept is Michael. They fall asleep in his apartment while waiting for him to come home, and like a fairytale they wake up in a different world, and we, the audience, wake up in a different movie. They are still in Michael's apartment, yes, but it appears that he has been expecting them and is ready and willing to be killed. The world stops. Michael bakes cookies.

The awful sadness that soaks the film from Michael's introduction on is powerful because it is set against the consequence-free movie-hitmen world we had been led into. It is remarkable that the about-face works so well. Even when the first world bleeds into the second, via a protracted encounter with a group of four rival hitmen (who seem to have wandered in from a Jim Jarmusch movie) also sent to kill Michael, the dislocation is complete. I felt a deeper suspense in the second world than would have been possible in the first.

The mystery of why Michael would want to be killed turns out to be almost no mystery. He is dying and has been unable to repair relations with his estranged daughter. In being killed he would get a quick exit and some cash to leave to her. At last it becomes apparent why Violet and Daisy have been established as so childlike, as they will be allowed, obliquely, a sliver of the love and guidance that Michael could not give his daughter. When, in the uncertain stasis in Michael's apartment, events seem to point to a disastrous fracture in Violet and Daisy's relationship, Michael can shepherd them through.

The character of the absent, innocent, noble father is perhaps not a new one, but it helps here that Michael is allowed to be wise without being overtly smart. The decisions he makes during our time with him are subtle; his big decisions are made. His almost childlike dictation to Violet of a heartbreaking letter to his daughter allows him to express the pure emotion that seems a distillate of everything he must have felt before we ever met him. He has become simpler and simpler, but like a pendulum the complexity and nuance has passed to Violet and Daisy. Why do you want to die, they ask throughout. Michael knows, but they cannot see it, and so they are not children any more.

Links: IMDb

Friday, September 23, 2011

Shame (2011)

The pivotal scene of "Shame" has Brandon (Michael Fassbender) and his boss David (James Badge Dale) watching Brandon's sister Sissy (Carey Mulligan) sing in a fancy, high-above-Manhattan cocktail lounge. She's singing a version of "New York, New York" in a fragile voice and at a glacial pace, wringing pathos from a song that might not deserve it. Director Steve McQueen fills the frame with Sissy's face for almost the whole protracted length of the song, her eyes flickering downward but with little expression. Only briefly are we allowed to glance away from Sissy to the table where David sits, like us, captivated, and Brandon cannot quite bear to watch.

We have been introduced to Brandon as a successful thirtysomething Manhattanite, living alone. We see him in the opening scenes padding naked around his apartment, watching porn, having sex with a prostitute, flirting silently on the subway. None of what we see seems seedy. He conspicuously and repeatedly ignores a message on his answering machine from a female voice, someone who clearly has strong feelings for him in some way. Celebrating success at work with his colleagues, he outflirts David before a group of women; when he leaves, one picks him up for some al fresco sex.

We learn that the voice on the answering machine is Sissy's. She appears in Brandon's apartment one day, surprising him despite the messages. We see her as emotive, demonstrative, playful - a musician, a performer - utterly at odds with Brandon. She is disruptive to him, but he allows her to stay for a time.

Later, in the lounge, as Sissy's song ends there are tears in Brandon's eyes. Why? Because he is forced, like us, to watch? Throughout the film we are permitted to sense some of what he feels for Sissy but we are never allowed to know why. If Brandon's shame relates directly to her, in any way - if it even has a source - we can only guess. David, on the other hand, is awed by Sissy's performance; whatever Brandon is being forced to feel, David, unencumbered, feels only attraction. David and Sissy openly flirt, and end up together, loudly, in Brandon's bed. Brandon is forced out, to run on the nearly empty, late-night Manhattan streets. McQueen shows us Brandon's run in a long, side-on tracking shot that reflects the long scene of Sissy's song. We saw her up close and static, but we see him in motion. Whatever he is feeling we have to infer from his movements.

Sissy becomes the object for David. Is this what Brandon cannot stand? His relationship with Sissy is the only real relationship we have seen him to hold, yet David sees her in the same way that we have seen Brandon look at prostitutes and strangers on the train. I found it almost maddening to guess whether Brandon was feeling possessiveness or was spurred to feel something about his own life. Whatever it is, it drives him for the rest of the film. He tries to establish a proper relationship with a coworker, and goes on a real date. But Sissy is there when he gets home, there to observe him, and perhaps there in his mind when he cannot consummate his new relationship. He seems unable to address his relationship to Sissy, and unable to establish a relationship with someone else.

In this limbo, "Shame" remains beautiful throughout. McQueen presents a New York that I saw as rich and flat, as if seen through a window. We first see Brandon from only the torso down, but by the end his face is profoundly unhidden, and the progression is matched by Fassbender's transition from feline assurance to unrestrained doubt.

I found it difficult to see "Shame" as an addiction movie, despite that Brandon is explicitly intended to be a sex addict. His behavior is certainly not normal - or at least it covers the whole spectrum of normalness from top to bottom - but the degree of his compulsiveness seems entirely reasonable. No revelations about addiction will be forthcoming; the film is infused with sex, but this is about the sibling relationship between Brandon and Sissy. She is undeniable, and he is defensive. McQueen and Mulligan combine to make Sissy magnetic, but still Brandon cannot be drawn in.

Links: IMDb

We have been introduced to Brandon as a successful thirtysomething Manhattanite, living alone. We see him in the opening scenes padding naked around his apartment, watching porn, having sex with a prostitute, flirting silently on the subway. None of what we see seems seedy. He conspicuously and repeatedly ignores a message on his answering machine from a female voice, someone who clearly has strong feelings for him in some way. Celebrating success at work with his colleagues, he outflirts David before a group of women; when he leaves, one picks him up for some al fresco sex.

We learn that the voice on the answering machine is Sissy's. She appears in Brandon's apartment one day, surprising him despite the messages. We see her as emotive, demonstrative, playful - a musician, a performer - utterly at odds with Brandon. She is disruptive to him, but he allows her to stay for a time.

Later, in the lounge, as Sissy's song ends there are tears in Brandon's eyes. Why? Because he is forced, like us, to watch? Throughout the film we are permitted to sense some of what he feels for Sissy but we are never allowed to know why. If Brandon's shame relates directly to her, in any way - if it even has a source - we can only guess. David, on the other hand, is awed by Sissy's performance; whatever Brandon is being forced to feel, David, unencumbered, feels only attraction. David and Sissy openly flirt, and end up together, loudly, in Brandon's bed. Brandon is forced out, to run on the nearly empty, late-night Manhattan streets. McQueen shows us Brandon's run in a long, side-on tracking shot that reflects the long scene of Sissy's song. We saw her up close and static, but we see him in motion. Whatever he is feeling we have to infer from his movements.

Sissy becomes the object for David. Is this what Brandon cannot stand? His relationship with Sissy is the only real relationship we have seen him to hold, yet David sees her in the same way that we have seen Brandon look at prostitutes and strangers on the train. I found it almost maddening to guess whether Brandon was feeling possessiveness or was spurred to feel something about his own life. Whatever it is, it drives him for the rest of the film. He tries to establish a proper relationship with a coworker, and goes on a real date. But Sissy is there when he gets home, there to observe him, and perhaps there in his mind when he cannot consummate his new relationship. He seems unable to address his relationship to Sissy, and unable to establish a relationship with someone else.

In this limbo, "Shame" remains beautiful throughout. McQueen presents a New York that I saw as rich and flat, as if seen through a window. We first see Brandon from only the torso down, but by the end his face is profoundly unhidden, and the progression is matched by Fassbender's transition from feline assurance to unrestrained doubt.

I found it difficult to see "Shame" as an addiction movie, despite that Brandon is explicitly intended to be a sex addict. His behavior is certainly not normal - or at least it covers the whole spectrum of normalness from top to bottom - but the degree of his compulsiveness seems entirely reasonable. No revelations about addiction will be forthcoming; the film is infused with sex, but this is about the sibling relationship between Brandon and Sissy. She is undeniable, and he is defensive. McQueen and Mulligan combine to make Sissy magnetic, but still Brandon cannot be drawn in.

Links: IMDb

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Drive (2011)

The Driver (Ryan Gosling) is economical of action when we see him at work. I found it easier to believe in him as an expert driver than if he had chattered and had his head on a swivel as in more whizz-bang car chases. Outside of the car he is equally reserved, using few words and leaving long pauses before speaking or acting. Perhaps this is why his decisions also seem so assured?

The Driver is introduced in a getaway job that immediately places the film's action as more Michael Mann than Michael Bay, and establishes the Driver as a craftsman. He is a wheelman, stunt driver, and mechanic, all in association with his mentor-like boss Shannon (Bryan Cranston). We see him perform a driving stunt on a movie set, and the Driver seems invincible behind the wheel. The distinction between legal and illegal is fuzzy; work is work. The same seems true for Bernie (Albert Brooks), who claims a former career as movie producer and now a middling criminal boss. Shannon talks him into bankrolling a stock car venture for the Driver.

The scheme will not see fruition. The Driver meets his neighbor Irene (Carey Mulligan) and bonds with her young son Benecio (Kaden Leos). Irene's husband Standard (Oscar Isaac) is in prison; she and the Driver form a friendship that is suggestive but decorous. The Driver is honorable and restrained.

Upheaval arrives when Standard is released, but thankfully not because Standard is angered by the interloper. His jealousy is allowed to flicker, but he too is allowed to be honorable and accepting. This becomes crucial. Standard is beaten and his family threatened; if he does not work to steal money to repay arbitrary prison protection fees, Irene and Benecio will be targeted. The Driver, with no explicit prompting, negotiates the job with himself as wheelman in exchange for Standard's debt to be considered repaid. In this way the mutual respect of the two men, through Irene, is the pivot on which the tragedy turns, as the "good" and simple heist goes wrong, and the consequences unfold.

But through it all the Driver consistently makes sensible choices (notwithstanding some of the vicious violence attached). We are told almost nothing about him in the film, yet he is permitted some open emotion that jars with the "anonymous stranger". What is going through his head? Early on the long, watchful pauses seem detached, maybe affected cool. As the Driver becomes more and more helpless to inevitability and the pauses are stoic and damp-eyed I wondered if maybe he was uncertain of himself all along. He is presented as a classic loner but ultimately seems lonely.

"Drive" reminded me a bit of another lonely film in "Lost in Translation". Some of the visuals parallel, especially the soft focus city-at-night scenes and the music was used in a way that felt similar. The tone of Irene's relationship with the Driver mirrors that movie too: it is brief, profound and restrained, although of course the characters are very different. Carey Mulligan seems not to take a deep breath throughout, Irene never totally relaxed and eventually drained by grief.

The Driver remains an expert to the end, but cannot end reassured. His best abilities and best-available decisions cannot salvage much from the inevitable path of events. Gosling shows this vulnerability and frustration with understatement, which is more than enough after the extreme reservation of the first half. The exception to this understatement is followed by the most poignant moment in "Drive". The Driver's most passionate outburst, of desire and violence, comes in an elevator with Irene and a man presumably sent to hurt them. Afterwards, Irene, grieving and freshly shocked, backs away and says nothing as the elevator door closes on the Driver. His reservation was briefly dropped, but his reward is to be left immediately speechless and alone. Later, after the story here is over, I wondered if he would have been changed by what happened, if the next person to meet him would see something that we didn't.

Links: IMDb, Metacritic

The Driver is introduced in a getaway job that immediately places the film's action as more Michael Mann than Michael Bay, and establishes the Driver as a craftsman. He is a wheelman, stunt driver, and mechanic, all in association with his mentor-like boss Shannon (Bryan Cranston). We see him perform a driving stunt on a movie set, and the Driver seems invincible behind the wheel. The distinction between legal and illegal is fuzzy; work is work. The same seems true for Bernie (Albert Brooks), who claims a former career as movie producer and now a middling criminal boss. Shannon talks him into bankrolling a stock car venture for the Driver.

The scheme will not see fruition. The Driver meets his neighbor Irene (Carey Mulligan) and bonds with her young son Benecio (Kaden Leos). Irene's husband Standard (Oscar Isaac) is in prison; she and the Driver form a friendship that is suggestive but decorous. The Driver is honorable and restrained.

Upheaval arrives when Standard is released, but thankfully not because Standard is angered by the interloper. His jealousy is allowed to flicker, but he too is allowed to be honorable and accepting. This becomes crucial. Standard is beaten and his family threatened; if he does not work to steal money to repay arbitrary prison protection fees, Irene and Benecio will be targeted. The Driver, with no explicit prompting, negotiates the job with himself as wheelman in exchange for Standard's debt to be considered repaid. In this way the mutual respect of the two men, through Irene, is the pivot on which the tragedy turns, as the "good" and simple heist goes wrong, and the consequences unfold.

But through it all the Driver consistently makes sensible choices (notwithstanding some of the vicious violence attached). We are told almost nothing about him in the film, yet he is permitted some open emotion that jars with the "anonymous stranger". What is going through his head? Early on the long, watchful pauses seem detached, maybe affected cool. As the Driver becomes more and more helpless to inevitability and the pauses are stoic and damp-eyed I wondered if maybe he was uncertain of himself all along. He is presented as a classic loner but ultimately seems lonely.

"Drive" reminded me a bit of another lonely film in "Lost in Translation". Some of the visuals parallel, especially the soft focus city-at-night scenes and the music was used in a way that felt similar. The tone of Irene's relationship with the Driver mirrors that movie too: it is brief, profound and restrained, although of course the characters are very different. Carey Mulligan seems not to take a deep breath throughout, Irene never totally relaxed and eventually drained by grief.

The Driver remains an expert to the end, but cannot end reassured. His best abilities and best-available decisions cannot salvage much from the inevitable path of events. Gosling shows this vulnerability and frustration with understatement, which is more than enough after the extreme reservation of the first half. The exception to this understatement is followed by the most poignant moment in "Drive". The Driver's most passionate outburst, of desire and violence, comes in an elevator with Irene and a man presumably sent to hurt them. Afterwards, Irene, grieving and freshly shocked, backs away and says nothing as the elevator door closes on the Driver. His reservation was briefly dropped, but his reward is to be left immediately speechless and alone. Later, after the story here is over, I wondered if he would have been changed by what happened, if the next person to meet him would see something that we didn't.

Links: IMDb, Metacritic

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

(poster)Shame_poster.jpg)